Is a picture worth a thousand words?

Jan 10, 2017

The saying "a picture is worth a thousand words" is often used to explain how a complex situation, idea, or thought can be conveyed better with a picture. There are many examples when this is true, such as a piece of art or a well-taken photograph expressing a range of emotions and feelings far better than any written words can.

There are also many examples when pictures can convey information more effectively within healthcare, such as the use of infographics and graphs to help disseminate scientific research or literature, like the excellent Yann Le Meur @YLMSportScience and Chris Beardsley @SandCResearch do so very well. There are also times when images can express an idea or message far quicker and easier than a blog or a podcast can such as my own 'physio treatment pyramid' or my 'road to recovery' pictures that I use a lot.

However, there are also many times when a picture is NOT worth a thousand words and when it does NOT covey complex information very well. Instead, some pictures can oversimplify, mislead, add more confusion and be more harmful than helpful. For example, in healthcare images of crumbling bones, red raw arthritic joints, and jam shooting out of a doughnut are often used in a belief they are helpful educational aids informing people about osteoporosis, arthritis, and spinal disc herniations, when in fact they are more likely to be harmful by painting misleading nocebic ideas about these conditions.

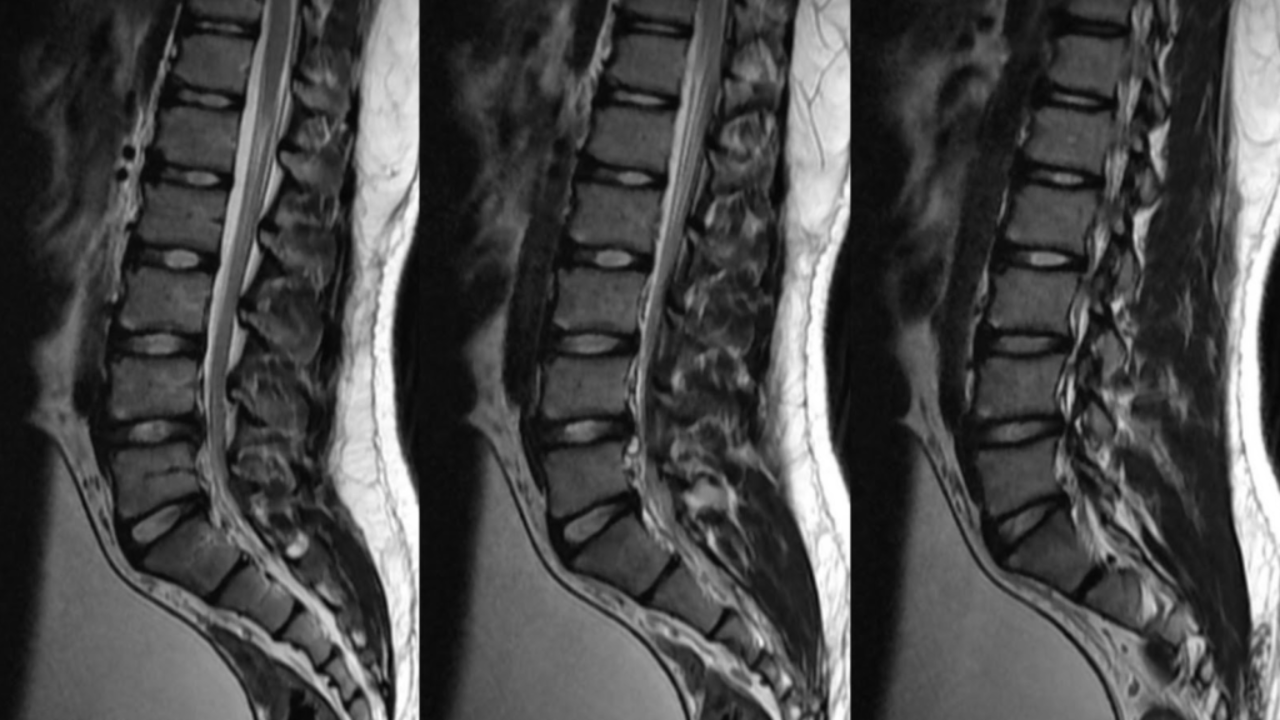

And these harmful misleading nocebic effects are not just seen with posters and infographics in healthcare, they are also, unfortunately, a very common side effect of many medical images used in healthcare such as Xrays, CT scans, MRI's and Ultrasounds.

Now there is no doubt that advances in medical imaging and technology have helped modern healthcare hugely. From the first accidental discovery of the X-Ray by Wilhelm Roentgen back in 1895 being quickly put to good use by battlefield surgeons to locate bullets and shrapnel in wounded soldiers, to the development of CT scans, MRIs, and ultrasounds to identify serious life-threatening diseases, illnesses, and injury's much faster and so have undoubtedly saved millions of lives. Simply put modern medical imaging has and will continue to be an invaluable tool... when used appropriately.

However, where medical imaging is failing many people is when it is being used inappropriately and incorrectly to explain why some things hurt in some people. This is due to many clinicians and patients thinking that pain and disability can be explained simply when a structural irregularity is seen on a scan such as a bulging or herniated disc, a misshapen or degenerative joint, or a torn or inflamed tendon, this, unfortunately, is just not true.

Now it can be this simple at times, for example, if you twist your ankle badly and have a lot of pain and can't walk on it, you get an X-ray that finds a broken bone, then the pain is undoubtedly due to your broken bone. However, there are also a lot of times when it's not this simple, such as when the pain starts without any clear injury or mechanism.

There is growing evidence that many things seen on scans in those with non-traumatic pain are found very commonly in people with NO pain and NO disability. We are beginning to recognise and understand that what we thought was pathology and sources of pain and other symptoms may just be normal variations in normal anatomy or natural ageing process.

For example, Guermazi et al (2012) demonstrated that ALL the common pathologies are seen in knee scans such as meniscal lesions, synovitis, and articular cartilage damage are found just as much, if not more often in subjects WITHOUT pain as those with pain. Also, Brinjiki et al (2014) showed that there is a high prevalence of structural irregularities of the lumbar spine seen on MRIs of more than 3000 people aged between 20 to 80 years olds who again had NO pain, disability or any other issues.

We also have a study by Nakashima et al (2015) who showed again high amounts of structural irregularities believed to cause pain and disability in the necks of over 1200 subjects who all again had NO symptoms or complaints. Then in the shoulder, we have Grisih et al (2011) who found a staggering 96% of subjects had at least one so-called pathology on their US scans yet zero pain or disability.

Again in the shoulder, we have Teunis et al (2015) who showed an increasing prevalence of rotator cuff tears with increasing age but more than 65% of them had no pain or disability. Then there is Schwartzberg et al (2016) who showed 72% of middle-aged subjects have non-symptomatic superior labral lesions, then Le Goff et al (2010) showed over 50% of those with calcific deposits in their rotator cuff tendons also had no pain or symptoms, and finally, Lesinak et al (2013) highlighting that nearly 50% of young elite-level professional baseball pitchers have full-thickness cuff tears and/or superior labral lesions with no pain or any adverse effect on their performance.

And this is just some of the evidence in the shoulder joint alone, I could go on and on presenting study after study conducted on pain-free, fully able subjects that shows so-called pathology in all areas of the body such as the hip, knee, foot, elbow and of course the spine! This large body of evidence available proves that many things we see on scans in those with pain and other symptoms are also seen just as often, if not more in those without any pain or symptoms.

Things often labelled as pathology on scans are often just normal variations in anatomy or morphology, or just normal signs of age. It is not as simple as just seeing a worn-out, misshapen, or torn structure on a scan and assuming it is the source of someone's pain.

A nice comparison here is looking at a photo of a wedding where everyone is grouped around the happy couple. In this photo, everyone is smiling and looking happy, but you cant determine who actually is happy just by looking at the photo. This is the same as when looking at an MRI of someone's spine or shoulder, we may see things that look unhappy on the scan, but we can't actually tell if it is actually unhappy just by looking at the scan.

This is why we should always medical imaging with a thorough physical examination and of course a full and detailed history from the patient. It's when all of these things combined fit together can we have more certainty and probability of what may or may not be contributing to someone's pain and disability.

Now, whilst we are on the subject of medical imaging I want to also talk about if scans can help reassure patients who have unexplained pains and other symptoms. Well, there is no doubt that if there is any significant probability that someone's pains and symptoms are coming from something serious or sinister that could adversely affect their quality of life or even threaten their life, then of course imaging can have a hugely important role here.

However, fortunately, these cases are rare and rarely are there any strong signs and symptoms of serious or sinister pathology in those we see with most musculoskeletal pains and disabilities. So should we send these people for scans anyway just to reassure them?

Well, simply no... there is little evidence that scans help reassure patients (ref), in fact, there is more evidence they can do the opposite and cause more fear, angst, and harm (ref). However, as always there is some nuance and shades of grey here.

The common misconception here is that it's the scan that is or isn't reassuring, when in fact it's actually the information and explanations given from the scan that is or isn't helpful or harmful. To put this as bluntly as I can... scans don't reassure or scare patients, clinicians explaining scan results do.

If scans are explained rationally and reasonably with the findings described in clear and easy-to-understand language, and most importantly put into context for the patient's age and their current situation, then yes I find scans can be really reassuring. However, if scan findings are read to patients using unclear and confusing medical terms without any context then they can absolutely scare the living shit out of people.

For example, there is a huge difference in telling a 65-year patient that their knee MRI has shown degenerative changes to their medial femoral condyle and a number of meniscal lesions, to their knee is showing normal age-related changes and no significant pathology that requires any invasive or surgical procedures.

When medical images are explained this way it has been shown in the research that patients are far less likely to progress onto unnecessary treatments and procedures and their prognosis and outcomes can be significantly better. And other research has shown that rewording scan reports with simpler terms such as changing the word tear for high signal, and degenerative for age-related it improves patient understanding and satisfaction.

So in summary we can see that pictures and images used in healthcare have both positive but also negative effects. I think all healthcare professionals have a responsibility to try and maximize the positive and reduce the negative when it comes to medical imaging. Clearly, medical imaging has a role, but it needs to be used wisely and sensibly.

I will leave you with the brilliant acronyms first used by Richard Heyward in his editorial on the issues of medical imaging in the British Medical Journal back in 2003 here. When it comes to medical imaging and scans do not B.A.R.F and create V.O.M.I.T, which stands for do not use Brainless Application of Radiological Findings and create Victims Of Modern Imaging Technology...

Or more simply never treat a scan, always treat the human!

As always thanks for reading

Adam

Stay connected with new blogs and updates!

Join my mailing list to receive the latest blogs and updates.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.

I hate SPAM, so I promise I will never sell your information to any third party trying to sell you laser guided acupuncture needles or some other BS.